MERYLISOLA.com

photographing humanity - मानवता का चित्र बनाना

Introduction

The world has turned a blind eye to violence against Muslims as a result of the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001. An unspoken global consensus was reached that Islamic terrorism is on the rise. Far-right movements with their “specific anti-Muslim agenda are gaining strength in Europe, US, Australia, Israel, and India with Islamophobes gaining power through the ballot box” (Ahmad, 2019). Protecting the human rights of Muslims is not a priority – we are an Islamophobic planet (Iftikhar, 2019). With this comes a worldwide silence and lack of action when Muslim populations experience genocide. The notion of “fighting terrorists” and increased spread of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment across the world have allowed oppressive regimes to get away with murder” (Ahmad, 2019). Currently, the Uighur Muslims of China and the Rohingya Muslims of Myanmar (formerly Burma) are undergoing similar processes of ethnic cleansing. The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defines genocide as the "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group" (United Nations, 1948). Both cases of China and Myanmar display clear evidence of genocide, however, the Chinese and Myanmar governments deny these accusations. In this report, I will prove genocide of Uighurs and Rohingya perpetrated by their governments, compare these cases as ethnic cleansing of Muslim populations, address genocide denial by the Chinese and Myanmar governments, and offer solutions to end the violence against these minority groups.

Uighur genocide

The Uighur ethnic group is a majority Muslim population in the Xinjiang region of northwestern China, officially known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). There are about 12 million Uighurs that call the XUAR home (BBC News, 2021). They speak their own language, similar to Turkish, and identify more with the cultures and ethnicities of Central Asian nations, as opposed to China’s (BBC News, 2021). The Uighurs attempted to gain independence during the 20thcentury, however, the region ended up falling into the control of China’s Communist government (BBC News, 2021). In recent decades, there has been a “mass migration of Han Chinese (China's ethnic majority) to Xinjiang, and the Uighurs feel their culture and livelihoods are under threat” (BBC News, 2021). While the Uighurs have always been a minority group in China, there have been new developments in anti-Muslim sentiment over the past few years. In 2017, President Xi Jinping released a statement saying that all religions in China should be “Chinese in orientation” which resulted in new crackdowns against Muslims (BBC News, 2021).Campaigners say that China is trying to “eradicate Uighur culture” (BBC News, 2021). A 2018 Human Rights Watch report found that the Chinese government was pushing for “repression against Xinjiang’s Muslims” and the “eradication of ideological viruses” (Iftikhar, 2019). As a result of this movement, more than one million Uighur people have been detained in concentration camps throughout the region. China refers to these camps as “re-education camps” and “counter-extremism centers” for the prevention of international Islamic terrorism, however, there is evidence of arbitrary detention, forced labor, and nonconsensual sterilization of Uighur women (BBC News, 2021). In December of 2020, research found that up to 500,000 people were being forced to pick cotton (BBC News, 2021). The Chinese government is using “systematic mass forced sterilization” and “coercive birth prevention policies to destroy the Uighur’s reproductive capacity” (Cotler & Diamond, 2021). Studies show 80% of all IUD placements in China have been placed in the Xinjiang province (Cotler & Diamond, 2021). As a result of this, between 2017 and 2019, the birth rate in the region declined by almost half. This is the “most extreme drop anywhere since the UN began recording these statistics” (Cotler & Diamond, 2021). Furthermore, Xinjiang did not include any birth rate data in its 2020 statistics (Cotler & Diamond, 2021). The Chinese Embassy in Washington D.C. even wrote on Twitter saying that Uighur women had been “emancipated” and “were no longer baby-making machines” (Wong & Buckley, 2021). The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide lists birth prevention targeting an ethnic group as an act that could qualify as genocide (Cadell, 2021). Islamic minorities are also disproportionately affected by newly enforced laws. Uighurs are at risk of detention for exceeding birth quotas, whereas elsewhere in China the punishment is a fine (Cadell, 2021). Exceeding birth quotas has also resulted in the separation of married Uighur couples (Cadell, 2021). There have been reports of forced marriages between Uighur women and Han Chinese men (Asat, 2020). Survivors of the Xinjiang internment camps reported: “physical, mental and sexual torture - women have spoken of mass rape and sexual abuse” (BBC News, 2021). Beijing has sentenced innocent Uighur people to years and even life in these concentration camps as well as prisons. This has led nearly 500,000 children to become orphaned (Asat, 2020). There were multiple accounts of Uighur prisoners being forced to eat pork and drink alcohol, both of which are forbidden for practicing Muslims (Iftikhar, 2019). The Chinese government has also eliminated the Uighur education system and destroyed the majority of Xinjiang’s sacred sites (Cotler, 2021).

Satellite photos show an increase in the number of concentration camps throughout Xinjiang.

The Wall Street Journal reported that the internment system is “designed to break down Uighur identity and denigrate Islam” (The Editorial Board, 2018). In one instance, “detainees were bound to chairs, deprived of adequate food and told ‘there is no such thing as religion’” (The Editorial Board, 2018). Leaked documents known as the China Cablesproved the camps intended to act as “high-security prisons” with strict punishments (BBC News, 2021). These concentration camps function to “rewire Uighur Muslims’ political thinking; erase their Islamic beliefs; and reshape their identities”, all of which equate to cultural genocide (Iftikhar, 2019). Senior Chinese officials have issued orders to “eradicate tumors”, “round up everyone”, “wipe them out completely”, and “break their lineage, break their roots, break their connections, and break their origins” (Cotler, 2021). Survivors who escaped the camps recollected guards saying they were following policies that indicated these programs would exist “until Uighurs would disappear… until all Muslim nationalities would be extinct” (Cotler, 2021). There is also evidence of a strong motivation to “dilute the Uyghur population, increase Han migration, and boost loyalty to the ruling Communist Party” (Cadell, 2021). Satellite photos show that this pattern of oppression is nowhere close to stopping. In 2020, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute found evidence of 380 new internment camps in Xinjiang – a 40% increase from previous camp numbers (BBC News, 2021). The US is one of the many countries that have accused China of committing genocide and crimes against humanity (BBC News, 2021). Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made a statement saying that Chinese officials were“engaged in the forced assimilation and eventual erasure of a vulnerable ethnic and religious minority group” (Wong & Buckley, 2021). The US State Department confirmed its determination of the violence against the Uighurs as genocide. Unfortunately, China is not part of the International Criminal Court (ICC), “the top international court that prosecutes genocide and other serious crimes, and which can only bring action against states within its jurisdiction” (Cadell, 2021). China is without a doubt guilty of ethnic cleansing, eugenics, and genocide against the Uighur people, however, the Chinese government remains safe from punishment.

Rohingya genocide

The Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar face a similar fate. This population has traced its origins in the region to the 15th century (Albert & Maizland, 2020). They differ from Myanmar’s “dominant Buddhist groups ethnically, linguistically, and religiously” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). Up until 2017, an estimated one million Rohingya were living in Myanmar’s southwestern Rakhine state (Albert & Maizland, 2020). The Burmese government rejects historical claims made by the Rohingya people and does not recognize them as one of the country’s 135 official ethnic groups (Albert & Maizland, 2020). As a result of this discrimination, the government refuses to grant citizenship to the Rohingya. This denial was part of Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law (Human Rights Watch, 2021). Most of the Rohingya population does not have any legal documentation, which deems them stateless peoples (Albert & Maizland, 2020). They are considered illegal immigrants originally from neighboring Bangladesh, despite clear evidence of their roots in Myanmar (BBC News, 2020). Furthermore, the Burmese government nor Rakhine’s dominant Buddhist group recognize the term/name “Rohingya” and therefore refuse to acknowledge the Rohingya as a community and grant them a collective political identity (Albert & Maizland, 2020). In recent years, the government has forced Rohingya to start carrying national verification cards that “effectively identify them as foreigners” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). Myanmar officials have claimed these cards are an “initial step towards citizenship”, however, critics believe that they “could make it easier for the government to further repress their rights” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). The government has also institutionalized its discrimination through “restrictions on marriage, family planning, employment, education, religious choice, and freedom of movement” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). It is a requirement that Rohingya seek permission from the government to wed, often meaning they must bribe authorities and “provide photographs of the bride without a headscarf and the groom with a clean-shaven face, practices that conflict with Muslim customs” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). In several towns in northern Rakhine state, couples are only allowed to have two children and before moving homes or traveling outside of their townships, Rohingya must get permission from the government (Albert & Maizland, 2020). These strict discriminatory policies have motivated Rohingya people to migrate abroad to Muslim-friendly counties such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand (Albert & Maizland, 2020). UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has identified the Rohingya as "one of, if not the most, discriminated people in the world" (BBC News, 2020).

Beginning in August of 2017, a month-long government crackdown by the Myanmar military, backed by local Buddhist mobs, led to the massacre of at least 6,700 Rohingya, 730 of whom were children under the age of five (BBC News, 2020). An estimated 288+ villages were “partially or totally destroyed by fire in northern Rakhine state” according to satellite imagery by Human Rights Watch (BBC News, 2020). Witnesses and survivors of the slaughter recalled, “Old men were decapitated, and young girls were raped, their headscarves torn off to use as blindfolds” (Beech et al., 2020). Private Myo Win Tun, a perpetrator of the Rohingya massacre, explained in his testimony, “We indiscriminately shot at everybody. We shot the Muslim men in the foreheads and kicked the bodies into the hole” (Beech et al., 2020). Win Tun received an order from his commanding officer to “Shoot all you see and all you hear” (Beech et al., 2020). Another soldier, Private Zaw Naing Tun, in a neighboring township said he and his comrades followed an almost identical directive from their superior to “Kill all you see, whether children or adults” (Beech et al., 2020). Witnesses said security forces used rifles, machetes, and flamethrowers (Beech et al., 2020). This mass violence triggered an exodus of Rohingya people to Bangladesh. This was one of the “fastest flights of refugees anywhere in the world” (Beech et al., 2020). Within a matter of weeks, an estimated 750,000 Rohingya were forced to abandon their homes in Myanmar (Beech et al., 2020). Security forces also opened fire on fleeing civilians and planted land mines along escape routes and the Myanmar-Bangladesh border (Albert & Maizland, 2020). Currently, 900,000 Rohingya are living in overpopulated refugee camps in Bangladesh (Human Rights Watch, 2021). According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Kutupalong Refugee Camp in Bangladesh is the largest refugee settlement in the world (BBC News, 2020). In March of 2019, the Bangladeshi government announced their nation will no longer accept Rohingya fleeing Myanmar (BBC News, 2020). There are still about 600,000 people remaining in Rakhine state who are at risk of government persecution and violence, forcibly confined to camps and villages, and without access to “adequate food, healthcare, education, and livelihoods” (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

In 2017, the US State Department said Myanmar had committed ethnic cleansing (Wong & Buckley, 2021). Antonio Guterres too has described the violence as ethnic cleansing and the humanitarian situation as “catastrophic” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). The UN described this as a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing" and the mass killings and rapes to be done with “genocidal intent” (BBC News, 2020). The International Court of Justice (ICJ) accused Myanmar of trying to “destroy the Rohingya as a group, in whole or in part, by the use of mass murder, rape and other forms of sexual violence, as well as the systematic destruction by fire of their villages” (Beech et al., 2020). In response to accusations of genocide from around the globe, Myanmar’s security forces claimed they were “carrying out a campaign to reinstate stability in the country’s western region” (Albert & Maizland, 2020). Unfortunately, like China, Myanmar is not a member of the ICC. However, the ICC claims they have some jurisdiction in this case because Bangladesh is a member nation (BBC News, 2020). This is a clear case of genocide against the Rohingya people that is a result of the Burmese government’s desire for a Buddhist country free from Islam.

Genocide denial

The Rohingya and Uighurs are experiencing similar processes of ethnic cleansing. They also share a pattern of genocide denial by their government perpetrators. Looking at China, the Chinese government insists that “Uighur militants are waging a violent campaign for an independent state by plotting bombings, sabotage, and civic unrest” and claim they are “combatting separatism and Islamist militancy in the region” (BBC News, 2021). China says its operations have helped the supposedly threatening Xinjiang situation and have “produced notable results” (Wong & Buckley, 2021). The government continues to deny all allegations of genocide (Wong & Buckley, 2021). China’s Foreign Ministry told Reuters in a statement, "The so-called ‘genocide’ in Xinjiang is pure nonsense. It is a manifestation of the ulterior motives of anti-China forces in the United States and the West and the manifestation of those who suffer from Sinophobia" (Cadell, 2021). The Ministry also called camp survivors who were raped and forcibly sterilized “actresses” (Cotler, 2021). China’s ambassador made a statement saying, “There is no such concentration camp in Xinjiang” and reports of detained Uighurs are untrue (BBC News, 2021). China says accusations of forced labor are "completely fabricated" and has dismissed claims that they are using forced mass sterilizations as a tactic to reduce the Uighur population (BBC News, 2021). The ministry said official Xinjiang birth rate data that showed a significant decrease from 2017 to 2019 “does not reflect the true situation” and “Uyghur birth rates remain higher than Han ethnic people in Xinjiang” (Cadell, 2021). In reaction to increased scrutiny, the Chinese government “expelled foreign journalists, scrubbed the internet of evidence, sanctioned and smeared parliamentarians and experts, and lectured other countries on mass atrocities and genocide” (Cotler, 2021). Furthering China’s capability to deny genocide, the country does not acknowledge the authority of the ICJ in questioning instances of genocide (Cotler, 2021). China is also a permanent member of the UN Security Council, which allows them to block any accusations of genocide that come from the ICC (Cotler, 2021).

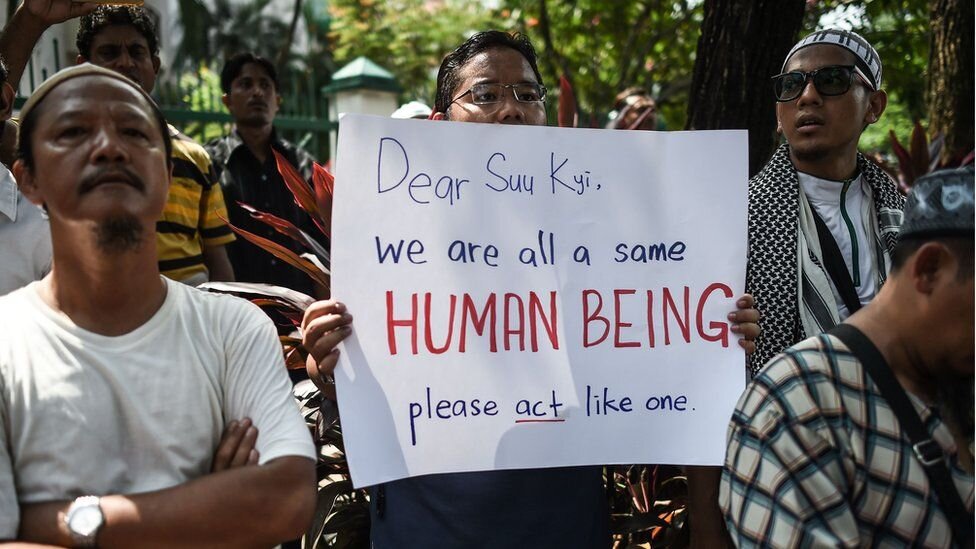

Identical to China, Myanmar also denies all allegations of genocide against the Rohingya (Beech et al., 2020). Aung San Suu Kyi, the State Counsellor of Myanmar, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and human rights icon, alsorejected accusations of genocide when she appeared at the ICJ in December of 2019 (BBC News, 2020). Once awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her non-violent fight for democracy and human rights, Suu Kyi has watched as her legacy has been ruined by her “support for the military and her refusal to vocally condemn the persecution of the Rohingya” (Beech et al., 2020). She also accused her critics of “fueling resentment between Buddhists and Muslims” in Myanmar (Albert & Maizland, 2020).Myanmar officials have suggested the Rohingya burned down their own villages “to garner international sympathy” (Beech et al., 2020). The army denies targeting civilians and claims they were fighting Rohingya militants (BBC News, 2020). Rayhan Asat, president of the American Turkic Lawyers Association and brother of Ekpar Asat (a Uighur currently imprisoned in a Xinjiang camp), effectively argues:

“Authoritarian governments often emulate one another; one can find many similar practices between Myanmar and China. Both governments target and persecute ethnic minorities that do not conform to their artificial ideals. Both vehemently deny the allegations while deploying similar strategies and forms of punishment. Both authorities label their genocidal campaigns internal security matters and reject public criticism from democratic countries. Both governments have justified their actions by claiming that the ethnic minorities are extremists, legitimizing ruthless human rights violations under the guise of counterterrorism” (Asat, 2020).

The Uighur and Rohingya cases are paralleled – these Muslim populations have synonymous experiences of oppression. Their governments have remained impregnable despite clear evidence of their guilt as perpetrators of cultural genocide and ethnic cleansing. Repeated denial of genocide will allow for the continuation of these human rights violations. The governments of China and Myanmar must be held accountable for their actions.

Moving forward

When examining why genocide occurs, political scientist Ben Valentino’s key argument is that elites matter. He says that society plays a smaller role in mass killing than is commonly assumed (Valentino, 2004). Genocide is a strategy or instrumental policy designed to accomplish leaders’ most important ideological or political objectives (Valentino, 2004). Therefore, the elites responsible for genocide must be held accountable and punished for their actions. The UN’s Human Rights Council investigative panel believes in Myanmar, “the country’s top generals should be prosecuted for genocide by the ICC or a special tribunal” (The Editorial Board, 2018). Leadership causing harm should be punished (The Editorial Board, 2018). While we saw a sign of hope for accountability after two Myanmar soldiers admitted to their crimes, confessions from first-hand perpetrators are not enough. It is more important that powerful elites who support and order the killing of Rohingya step forward and admit their responsibility for these atrocities. If they do not, genocide is bound to continue. This is the same for the Uighur case as well. Chinese elites must own up to their political agenda that included genocidal intent and commands. In addition, “Robust and consistent attention from the United Nations is a must” (The Editorial Board, 2018). Institutions whose duties are to protect human rights and prevent genocide must ensure elites are charged with the crimes they’ve committed. While “Sanctions and condemnation from Washington and other world capitals may not rescue these Muslim minorities… they are worth a try” (The Editorial Board, 2018). Payam Akhavan, a Canadian lawyer representing Bangladesh in a filing against Myanmar at the ICC, said, “Impunity is not an option. Some justice is better than no justice at all” (Beech et al., 2020). Accountability is critical to the prevention of further and future atrocities (Beech et al., 2020).

Another powerful factor in ending these genocides is the power of naming them as such. Labeling the Rohingya and Uighur violence and ethnic cleansing as genocide offers validation to those suffering and allows the opportunity to stop these crimes. Many Uighurs expressed a great deal of gratitude for the US State Department’s determination that China is committing genocide and crimes against humanity in its treatment of their people (Wong & Buckley, 2021). Rayhan Asat reflected:

“Today’s determination of genocide is a signal of recognition to the long suffering of victims and survivors of the Chinese government’s internment camps, like my brother Ekpar, and millions of Uighurs. It is the starting point on the road to justice, freedom, and accountability for these atrocities” (Wong & Buckley, 2021).

Ziba Murat, a US resident whose mother is imprisoned in Xinjiang, said, “This gives us hope that those who have attempted to water down what is happening with the destruction of our people can no longer hide their complicity” (Asat, 2020). A successful finding of genocide would also help the Rohingya as it “would send a message that perpetrators cannot commit the crime of all crimes with impunity and bring some sense of justice to Rohingya victims” (Asat, 2020). Asat argues further that it would be a “heartwarming signal” to the Uighur community that the ICC holds nonmember states accountable for their atrocities, even if they are economically and politically powerful like China (Asat, 2020). This action would bring “some form of comfort to victims in their pursuit of justice” (Asat, 2020). Naming atrocities as genocides carries with it the power to give a voice to the voiceless, end violence and the suffering that comes with it, and the opportunity to learn from what happened to help prevent genocides in the future.

Lastly, Muslim solidarity and resistance through an ethic of love are crucial to eradicating genocide and building resilience in affected communities. People have power in numbers. We are all links in a chain. Therefore, joining together as Muslims with the motive to end oppression and violence against them is extremely powerful. It is time that “Muslims together with other communities expose the injustice, hypocrisy, and double standards in international relation and make these leaders and states accountable” (Ahmad, 2019). Furthermore, political sociologist Dr. Marie Berry says an ethic of love makes it possible to resist the oppression and exploitation of others (Berry, 2021). A culture of domination is anti-love, however, choosing love disrupts that politic of domination (Berry, 2021). The root of resistance is love and the more love is built up within the Rohingya and Uighur communities, the more successful they will be in defying the powers that hold them down. The more Muslim solidarity is built, the more global solidarity will be established as well. The more love that grows the more gravity these cases of genocide and human rights violations will gain. The more love there is throughout the globe, the more likely it is the Uighurs and Rohingya will see justice. The more love that exists, the less discrimination and hate will be welcomed on our planet, and thus the possibility for future genocides will diminish. The more love prevails, the better chance humanity has at a world free from genocide.

SOURCES

Ahmad, Zia. (2019). Palestinians, Rohingyas, Uyghurs, and now Kashmiris: Victims of Might is Right. Australasian Muslim Times.

The Editorial Board. (2018). Persecuted Muslims: Atrocities in Myanmar, abuses in China. Chicago Tribune.

Murphy, Ann M. (2020). Islam in Indonesian Foreign Policy: The Limits of Muslim Solidarity for the Rohingya and Uighurs. The Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

Asat, Rayhan. (2020). China and Myanmar face Uighurs and Rohingya that are fighting back after years of oppression. NBC News.

Iftikhar, Arsalan. (2019). It’s time to stop ignoring China’s cultural genocide of Uighur Muslims. Think.

BBC News. (2021). Who are the Uighurs and why is China being accused of genocide? BBC News.

Cadell, Cate. (2021). EXCLUSIVE China policies could cut millions of Uyghur births in Xinjiang. Reuters.

Wong, Edward & Buckley, Chris. (2021). U.S. Says China’s Repression of Uighurs Is ‘Genocide’. The New York Times.

Cotler, Irwin & Diamond, Yonah. (2021). China’s Uyghur Genocide Is Undeniable. Project Syndicate.

Albert, Eleanor & Maizland, Lindsay. (2020). The Rohingya Crisis. Council on Foreign Relations.

Beech, H., Nang, S. & Simons, M. (2020). ‘Kill All You See’: In a First, Myanmar Soldiers Tell of Rohingya Slaughter. The New York Times.

BBC News. (2020). Myanmar Rohingya: What you need to know about the crisis. BBC News.

Human Rights Watch. (2021). Rohingya. Human Rights Watch.

Valentino, Benjamin A. (2004). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20thCentury. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs.

Berry, Marie. (2021). Why an ethic of love? Love, Resilience, & Creativity During Genocide and Mass Atrocities. Week one.

United Nations. (1948). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.